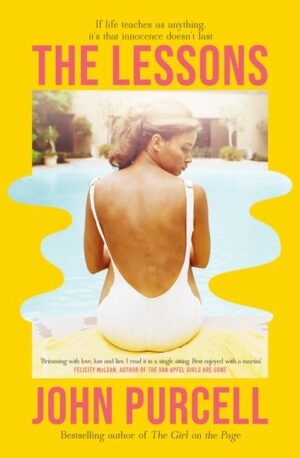

- The Girl on the Page is set in the publishing world. Jane Curtis, one of the main characters in your new book The Lessons, is a novelist. What draws you to writers in your fiction?

I recently unpacked over a hundred boxes of books. Putting them up on the shelves in our new house, it became clear that my main obsession was fiction. But a close second was the lives of writers. I have more biographies of novelists than any other subject. And memoirs and diaries, too. When I first started to write, when I was eighteen or nineteen, I bought such books because I was devouring fiction and always wondering – how did they do that? But you learn fairly quickly there is no easy answer to that. Biographies ceased to be learning tools and became a source of consolation and encouragement. All novelists are fascinating to me - whether literary or commercial, hugely successful or loved by a select few. No writing life is like another. I write about writers because writers can be anything, they can know anything, and their histories can be whatever I want them to be because a writer can emerge from any environment. This brings me a great freedom when writing about writers. But the main thing, the reason I am endlessly fascinated by writers, is they often exist in moral void, they are both in life and outside of it at the same time. Any kind of odd behavior can be explained away by the designation, writer. You can’t entirely trust them because you never quite know what they believe, what they know, or what they are capable of doing. And that makes for great fiction. - At heart, The Lessons is a love story, but you don’t strike me as a romantic, how did the story of Harry and Daisy relationship come about?

I have always loved a good romance. One of my favourite novels is Austen’s Persuasion, another is Forster’s A Room with a View, a novel I have read more times than any other. In both of these books the heroine is convinced by well-meaning friends that her love for the hero is a passing fancy, something to be outgrown. Anne Elliot from Persuasion renounces all hope of love and devotes herself to others. Lucy Honeychurch from A Room with a View gets engaged to a man who can’t love. They don’t know it yet, but their rejection of love has made their lives meaningless. Sometimes we are too young to appreciate how rare love is. So when I brought Harry and Daisy together in The Lessons, I knew I would tear them apart as Austen and Forster had done. I wanted them to learn what a life without love was like. I wanted them to learn how lucky they were to find love at all. - There are four first person narrators in The Lessons, three narrating events in the sixties and one in the early eighties. Tell my why you decided to write the story in this manner.

Harry came first. I once wrote a story about an old man with a secret returning to the village of his birth in the hope of finding peace, redemption or revenge? I don’t know which, I never finished the story. When I moved to the UK and found myself living in the gorgeous countryside of the Kent Downs, the old man returned, but he was no longer old, he was young and he had a story to tell me. The secret he hadn’t been able to share. That’s when he first told me about Daisy. Then came Simon. He wasn’t that interested in Harry, but he had a story to tell, and that story also involved Daisy. Of course, Daisy wasn’t going to let two men tell her story. Besides, what could a man ever know about the heart of a woman? So Daisy started to tell the story from the beginning, setting things straight. Trouble was, Daisy’s aunt Jane Curtis was not very happy about how she was being portrayed in all of these narratives, so she turned up when I thought the whole story had been told and began telling it her way. So that’s how things happened. I wrote each narrative separately. I gave them each free reign then plaited the book together with the separate strands. The hope was that by giving them each space, the truth of the matter would emerge whether they liked it or not. - Jane Curtis is a character readers will love to hate, or hate to love, was she based on real life writer? Edna O’Brien, perhaps?

Jane Curtis isn’t based on any writer. Or more to correctly, Jane Curtis is based on dozens of writers. Like many writers she is an uneasy mix of raw talent and self-doubt, of daring and cowardice, of honesty and deception. Having long been a fan of women writers of the period, I found researching women and women writers of the sixties fascinating. As a woman Jane’s wins are belittled and her mistakes are judged more harshly. But she manages to produce work that is admired in the face of unwavering opposition. In this respect, she is like Edna O’Brien, but also a dozen other writers of that period. As women they had to forge a place in the literary world that did not want to admit them with nothing more than bloody-mindedness. All while living in an era of great social change, in which the role of women seemed to change day by day. As to whether one should love or hate her, I hope I’ve shown her to be human, which is to say we should try to love her as we would hope to be ourselves regardless of our flaws. - You recently left Australia to live in the UK and were writing The Lessons throughout the pandemic, what influence did the tragic loss of life in the UK and the various lockdowns have upon your writing?

I know some writers found the restrictions of lockdowns left them barren. That the horrid state of the world left them too anxious to write. A fate I might so easily have shared. The state of the world makes me very anxious but I was contracted to write another book and I was already late by the time Covid struck. So lockdown actually worked in my favour. I know how horrible that sounds. I couldn’t go anywhere. I couldn’t do anything. I had no excuse not to write. And thank god I did, I don’t think I would have made it through these awful months, now years, if I didn’t have my writing to disappear into.

Order your copy of The Lessons here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed