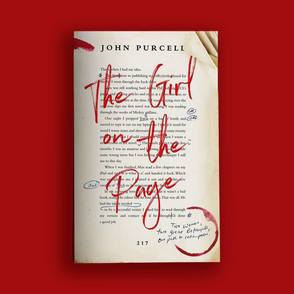

As we near publication of my new novel, The Girl on the Page, I cannot but stop to wonder where the book came from. I wrote the novel so quickly. It just fell onto the page. Almost as if I had been researching it for years. But I hadn’t. I had just been working away at my day job selling books.

Then it hit me. Rather belatedly, I’ll admit – everything I had done up till now had been research for The Girl on the Page.

I spent the greater part of my twenties and thirties sitting behind the counter in a second-hand bookstore. First someone else’s, then my own. Second-hand bookselling looks a lot like normal bookselling to the untrained eye, but they are nothing alike. And neither are the customers.

Second-hand bookshops are not viable businesses. But somehow they always seem to limp on. Mine teetered on the edge of oblivion for the full ten years of its existence. It never fell in. The end came when building owners tore the building down. I had no option but to get out of their way. By then I’d had enough of living hand to mouth, so decided to become a full time writer. This reasoning still makes me laugh.

Those ten years sitting in my bookshop were my education. I learnt more than I can say. My teachers were the eccentrics who visited regularly. And they were eccentric. Every sort of misfit, creep, loser and cracked genius would venture in. The world’s outcasts desperate for the lifegiving air of a musty secondhand bookshop.

Some of my teachers wore the outer garments of the everyday man and woman, but this would be pulled aside as soon as they entered. Then they would air their grievances, or lose themselves in some trancelike hymn to the last book they had read, or they would take umbrage over one of my eccentric book cataloging decisions. The greatest teachers were the idealists, the artists, the true believers. Their unbending natures in a world of bending reeds excited my imagination like no others.

It was their recommendations I heeded. The old man with a permanent drip hanging from the end of his nose who spoke of Jung and chemistry and forced me to take home all of the works of John Cowper Powys. The angry woman who made me read The Egoist by George Meredith. The white-haired woman who spoke little and read much, who placed a copy of Dreiser’s An American Tragedy on my desk and made me promise to read it without asking what it was about. The best advice. And the woman who overheard my conversations with other customers and brought Of Human Bondage to the counter saying it was the only great book she had ever read and wanted to know if I thought it was great, too. It was.

Then there were the shelves themselves. The hours in a second-hand bookshop are twice as long as the hours outside the shop and I would peruse my own shelves and listen to the books chatter as I passed. As I read more and spoke more with my oddbod teachers, the shelves grew more talkative. I heard Willa Cather and Edith Wharton arguing, the incessant chatter of Christina Stead’s House of All Nations and the urgent whispers of Gautier’s Mademoiselle de Maupin.

My new novel, The Girl on the Page, is born from these experiences. This is where the hearts of the two of main characters, literary giants, Helen Owen and Malcolm Taylor were forged. Their knowledge and wisdom, too. And their integrity. Without my second-hand bookstore education, I could not have created them. I love them and all they stand for more than I can say.

Helen and Malcolm ask the question at the centre of the novel: what do we lose when we sell out? Because I love them, I feel cruel asking them to act out the answer to this question, but it is a question that needs to be answered in this increasingly opportunistic age.

Amy Winston is the other main character of The Girl on the Page, she works in publishing and is very much born of this age. Or at least so she appears on first meeting her. She is damaged and we meet her mid-decline. To create Amy Winston and her world I have drawn from more recent experience.

Since leaving the second-hand bookshop I have become unrecognisable to myself. I have become the book guy at Australia’s fastest growing online bookshop. I have published a series of erotic novels under a pseudonym. I have met and interviewed hundreds of authors and celebrities. I have worked closely with every major publisher in the country. And I rarely read a book by a dead person.

The Girl on the Page describes what happens when these two worlds collide.

(First published on the The Booktopian)

Then it hit me. Rather belatedly, I’ll admit – everything I had done up till now had been research for The Girl on the Page.

I spent the greater part of my twenties and thirties sitting behind the counter in a second-hand bookstore. First someone else’s, then my own. Second-hand bookselling looks a lot like normal bookselling to the untrained eye, but they are nothing alike. And neither are the customers.

Second-hand bookshops are not viable businesses. But somehow they always seem to limp on. Mine teetered on the edge of oblivion for the full ten years of its existence. It never fell in. The end came when building owners tore the building down. I had no option but to get out of their way. By then I’d had enough of living hand to mouth, so decided to become a full time writer. This reasoning still makes me laugh.

Those ten years sitting in my bookshop were my education. I learnt more than I can say. My teachers were the eccentrics who visited regularly. And they were eccentric. Every sort of misfit, creep, loser and cracked genius would venture in. The world’s outcasts desperate for the lifegiving air of a musty secondhand bookshop.

Some of my teachers wore the outer garments of the everyday man and woman, but this would be pulled aside as soon as they entered. Then they would air their grievances, or lose themselves in some trancelike hymn to the last book they had read, or they would take umbrage over one of my eccentric book cataloging decisions. The greatest teachers were the idealists, the artists, the true believers. Their unbending natures in a world of bending reeds excited my imagination like no others.

It was their recommendations I heeded. The old man with a permanent drip hanging from the end of his nose who spoke of Jung and chemistry and forced me to take home all of the works of John Cowper Powys. The angry woman who made me read The Egoist by George Meredith. The white-haired woman who spoke little and read much, who placed a copy of Dreiser’s An American Tragedy on my desk and made me promise to read it without asking what it was about. The best advice. And the woman who overheard my conversations with other customers and brought Of Human Bondage to the counter saying it was the only great book she had ever read and wanted to know if I thought it was great, too. It was.

Then there were the shelves themselves. The hours in a second-hand bookshop are twice as long as the hours outside the shop and I would peruse my own shelves and listen to the books chatter as I passed. As I read more and spoke more with my oddbod teachers, the shelves grew more talkative. I heard Willa Cather and Edith Wharton arguing, the incessant chatter of Christina Stead’s House of All Nations and the urgent whispers of Gautier’s Mademoiselle de Maupin.

My new novel, The Girl on the Page, is born from these experiences. This is where the hearts of the two of main characters, literary giants, Helen Owen and Malcolm Taylor were forged. Their knowledge and wisdom, too. And their integrity. Without my second-hand bookstore education, I could not have created them. I love them and all they stand for more than I can say.

Helen and Malcolm ask the question at the centre of the novel: what do we lose when we sell out? Because I love them, I feel cruel asking them to act out the answer to this question, but it is a question that needs to be answered in this increasingly opportunistic age.

Amy Winston is the other main character of The Girl on the Page, she works in publishing and is very much born of this age. Or at least so she appears on first meeting her. She is damaged and we meet her mid-decline. To create Amy Winston and her world I have drawn from more recent experience.

Since leaving the second-hand bookshop I have become unrecognisable to myself. I have become the book guy at Australia’s fastest growing online bookshop. I have published a series of erotic novels under a pseudonym. I have met and interviewed hundreds of authors and celebrities. I have worked closely with every major publisher in the country. And I rarely read a book by a dead person.

The Girl on the Page describes what happens when these two worlds collide.

(First published on the The Booktopian)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed