I’ve been reading a lot of biographies and memoirs of novelists. They don’t make for uplifting reading. I mean honestly, what a miserable bunch writers are. Moan moan, drink drink, write write. Never satisfied. Always seeking out greener pastures. Boring everyone to death with their thoughts, boring them even deader with their silence. Their interminable reading. And that tap, tap, tap, or scribble, scribble, scribble and shouts for silence echoing down the hall. All the while torn between incompatible futures – that of austere artistic merit and the esteem of the few or the abuse of talent and shameless wealth and lonely fame. Both futures lined with the same milestones – divorce, financial disaster, anxiety over legacy, obscurity, addiction, illness, despair – leading to the same place, the grave.

Of course it isn’t all doom and gloom. Some get cut down in their prime. Like that newly published writer who was killed by a falling branch while walking down the Champs Elysees. I don’t recall his name.

No, you’re right, maybe I am choosing the wrong writers. I am a miserable bastard myself. It’s probably just unconscious bias. I’m drawn to the worst of them. There are probably hundreds of happy writers and as many biographies of them. Case in point, there’s a biography of Henry Miller on my shelf called The Happiest Man Alive. He’s dead now, too.

Even though I know how it always goes, I can’t help reading about them. There is just something fascinating about writers. At least to me. They are such odd bods. Walking contradictions. Brilliant and stupid. Exciting and dull. Observant and yet so blind. Especially to their own faults and their own talents.

I am talking of a certain subset of novelists. I can admit it. Not all writers wrestle with their own devils. Not all are artists. Some start out with no integrity so don’t live in fear of losing it. In fact the vast majority do their best, succeed or fail, potter about, develop a small following, get bored of financial insecurity and go back to the work they did before. Those few who succeed beyond their own expectations and actually make some money from their work try very hard not to disappoint their readership and present them each year with the same novel in different guises.

My 2018 novel, The Girl on the Page, dealt with all this – miserable writers, artistic integrity, the lure of commercial success, the publishing machine and literary prizes. So you would expect I was done with writers in my novels. But you’d be wrong.

Just as I can’t stop reading about writers, I can’t stop writing about them either.

When I wasn’t looking, a novelist snuck in the back door of my new novel The Lessons and proceeded to take over. Her name is Jane Curtis and she is a piece of work. But I kind of like her. The novel centres on the love affair of two young people, Daisy and Harry. It was almost a romance novel before Jane Curtis turned up and did what all novelists do, stuck her nose where it didn’t belong and brought pain and misery to everyone she claimed to love. But she does all this with such flair that we can almost forgive her.

The truth is, the novel just didn’t work until Jane turned up.

I have always been fascinated by stories that seem to be aware they are stories. The multiple endings to John Fowles’ French Lieutenant’s Woman, Kurt Vonnegut inserting himself into the narrative of Breakfast of Champions so he can be there when his two main characters finally meet, that sort of thing. Jane gave me the opportunity to play in my own small way.

The bulk of The Lessons is set in the 1960s, Jane’s first person narrative is set in the 1980s and interrupts the main narrative from time to time. A novelist in a novel will always bring an element of self-consciousness to a narrative. Throughout the 1960s storyline Jane is writing novels based on the events we are reading about. The reader is invited to reflect on what they are being told in light of this.

I feel I must have been influenced by E.M. Forster’s use of novelist Eleanor Lavish in A Room with View. As witness to events in the first half of the novel, Lavish is able to effect change, albeit unwittingly, in the second half of the novel, even though she herself doesn’t appear, because her much disparaged novel is read aloud to the main characters, and that novel contains a description of a kiss everyone has been trying very hard to pretend never happened.

The reading aloud of Lavish’s novel forces Forster’s characters to interrogate the stories they have been telling themselves. Stories within stories. We are all novelists. Some are just better than others.

Throughout The Lessons, with each of Jane’s interruptions, I hope the reader will become more and more conscious of her attempts to control the narrative. I found her voice irresistible. I gave way to her more times than I’m ready to admit. I ask the reader to keep their wits about them. But then, to my mind, there is no better narrator than a novelist. Who better to tell us the whole truth than a professional liar?

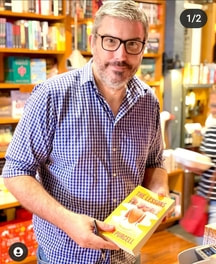

--The Lessons by John Purcell (HarperCollins Australia) is out now.

Of course it isn’t all doom and gloom. Some get cut down in their prime. Like that newly published writer who was killed by a falling branch while walking down the Champs Elysees. I don’t recall his name.

No, you’re right, maybe I am choosing the wrong writers. I am a miserable bastard myself. It’s probably just unconscious bias. I’m drawn to the worst of them. There are probably hundreds of happy writers and as many biographies of them. Case in point, there’s a biography of Henry Miller on my shelf called The Happiest Man Alive. He’s dead now, too.

Even though I know how it always goes, I can’t help reading about them. There is just something fascinating about writers. At least to me. They are such odd bods. Walking contradictions. Brilliant and stupid. Exciting and dull. Observant and yet so blind. Especially to their own faults and their own talents.

I am talking of a certain subset of novelists. I can admit it. Not all writers wrestle with their own devils. Not all are artists. Some start out with no integrity so don’t live in fear of losing it. In fact the vast majority do their best, succeed or fail, potter about, develop a small following, get bored of financial insecurity and go back to the work they did before. Those few who succeed beyond their own expectations and actually make some money from their work try very hard not to disappoint their readership and present them each year with the same novel in different guises.

My 2018 novel, The Girl on the Page, dealt with all this – miserable writers, artistic integrity, the lure of commercial success, the publishing machine and literary prizes. So you would expect I was done with writers in my novels. But you’d be wrong.

Just as I can’t stop reading about writers, I can’t stop writing about them either.

When I wasn’t looking, a novelist snuck in the back door of my new novel The Lessons and proceeded to take over. Her name is Jane Curtis and she is a piece of work. But I kind of like her. The novel centres on the love affair of two young people, Daisy and Harry. It was almost a romance novel before Jane Curtis turned up and did what all novelists do, stuck her nose where it didn’t belong and brought pain and misery to everyone she claimed to love. But she does all this with such flair that we can almost forgive her.

The truth is, the novel just didn’t work until Jane turned up.

I have always been fascinated by stories that seem to be aware they are stories. The multiple endings to John Fowles’ French Lieutenant’s Woman, Kurt Vonnegut inserting himself into the narrative of Breakfast of Champions so he can be there when his two main characters finally meet, that sort of thing. Jane gave me the opportunity to play in my own small way.

The bulk of The Lessons is set in the 1960s, Jane’s first person narrative is set in the 1980s and interrupts the main narrative from time to time. A novelist in a novel will always bring an element of self-consciousness to a narrative. Throughout the 1960s storyline Jane is writing novels based on the events we are reading about. The reader is invited to reflect on what they are being told in light of this.

I feel I must have been influenced by E.M. Forster’s use of novelist Eleanor Lavish in A Room with View. As witness to events in the first half of the novel, Lavish is able to effect change, albeit unwittingly, in the second half of the novel, even though she herself doesn’t appear, because her much disparaged novel is read aloud to the main characters, and that novel contains a description of a kiss everyone has been trying very hard to pretend never happened.

The reading aloud of Lavish’s novel forces Forster’s characters to interrogate the stories they have been telling themselves. Stories within stories. We are all novelists. Some are just better than others.

Throughout The Lessons, with each of Jane’s interruptions, I hope the reader will become more and more conscious of her attempts to control the narrative. I found her voice irresistible. I gave way to her more times than I’m ready to admit. I ask the reader to keep their wits about them. But then, to my mind, there is no better narrator than a novelist. Who better to tell us the whole truth than a professional liar?

--The Lessons by John Purcell (HarperCollins Australia) is out now.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed